A powerful synergy results when combining the power, reliability, portability, and rich library set of the Java platform with the power and flexibility of JRuby. This article will discuss a couple of ways in which JRuby surpasses Java as a programming language for the JVM:

- Code as first class objects – code blocks, lambdas, and procs can exist and be passed around for the most part like any other objects. There is no need to create a class to contain them as there is in Java.

- Syntactic sugar for the specification of hash values as parameters – hash (map, in Java lingo) key/value pairs can be passed to a function literally, and the function will receive them as a single hash. In other words, they can be passed without the need for the programmer to create and populate a hash instance.

In order to contrast Java and JRuby, and showcase the above features, we will implement a Fahrenheit/Celsius temperature converter in both Java and JRuby that uses Java Swing as its GUI library. The source code can be found at http://is.gd/n3Je. (The Git repo main page for this project is at http://github.com/keithrbennett/multilanguage-swing. The README file has instructions for how to run the Java, Ruby, and Clojure versions.

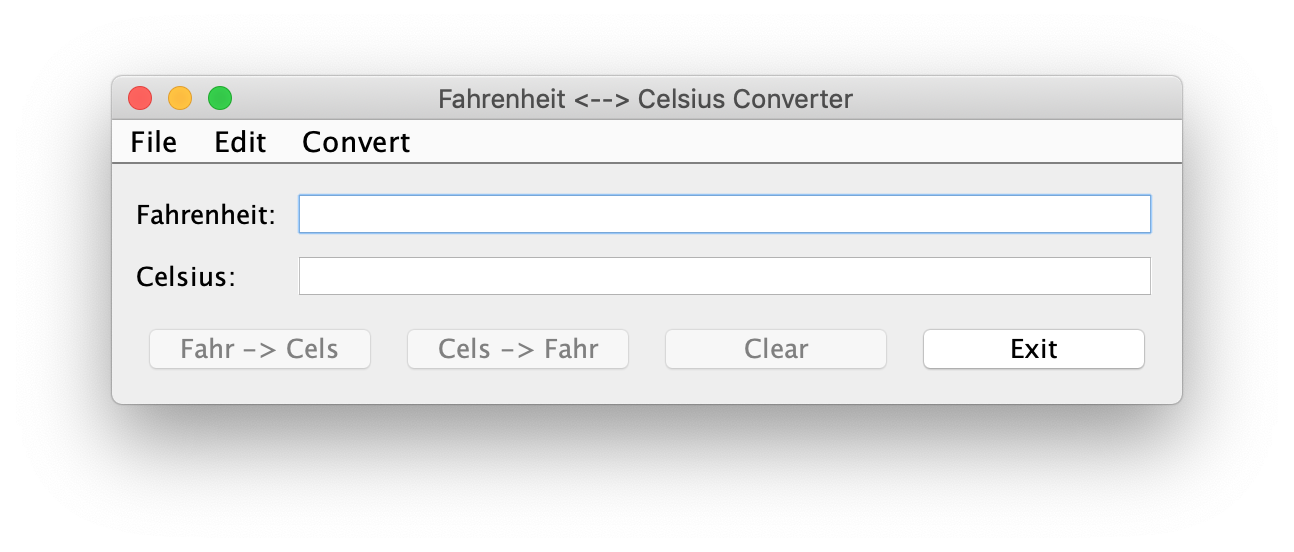

Here is an image of the application’s sole window. There are text fields for entering the temperature, and buttons and menu items to perform the conversions, clear the text fields, and exit the program.

We’ll get to JRuby soon, but first a little about the Swing issues we’ll be addressing in comparing JRuby with Java.

Swing enables the sharing of behavior among visual components such as menu items and buttons via the sharing of Action objects (or, to be precise, implementations of the javax.swing.Action interface). So, for example, in this app there is a single Exit action object shared by both the Exit button and the Exit item of the File Menu (that is, both the button and menu item contain references to the same action).

When an action is modified, as, for example, to enable or disable it, then all components expressing that action modify their state and appearance accordingly. When the program starts up, the conversion and clear buttons’ actions are not appropriate given that both text fields are empty; therefore, those actions are disabled. Although you can’t see it in this picture, in addition to the buttons being disabled, the corresponding menu items are disabled as well.

Swing is pretty good about conforming to the MVC (model/view/controller) principle. Even the lowly text field contains a reference to a model, which is an implementation of the javax.swing.text.Document interface. You can attach listeners to this model, so that when the text changes you can inspect the contents and respond accordingly. (A common Swing programming mistake is to listen to keyboard events instead, but this does not catch some cut and paste events, nor the programmatic setting of the content.)

These two Swing features enable the effective, clean, and dry implementation of enabling and disabling of action components based on the program’s state at any given time. We merely attach document listeners to the text fields that hook into text changes, and enable or disable the actions as appropriate when they are called.

Unfortunately, the Swing DocumentListener interface requires implementing behavior for three different types of text events (change, insert, and remove), and provides no way to simply specify a single behavior that will be applied to all three. (In fact, in several years of Swing programming I never encountered a case where the respective events needed to be handled differently, for performance or any other reason.) We will therefore create an adapter that remedies this. The implementations of this adapter in Java and JRuby will highlight the greater flexibility of JRuby through its support of code blocks as first class objects and its syntactic sugar that makes passing hash entries more natural.

The Java adapter is implemented here as the SimpleDocumentListener that implements DocumentListener. It has a single abstract method that must be implemented by its subclasses, and delegates to that method from all three DocumentListener interface methods. Note that it is necessary to create a new class inheriting from SimpleDocumentListener in order to use it. Here is the code:

import javax.swing.event.DocumentEvent;

import javax.swing.event.DocumentListener;

/**

* Simplifies the DocumentListener interface by having all three

* interface methods delegate to a single method.

*

* To use this abstract class, subclass it and implement the abstract

* method handleDocumentEvent().

*/

public abstract class SimpleDocumentListener implements DocumentListener {

/**

* Implement this method when subclassing this class.

* It will be called whenever a DocumentEvent occurs.

*/

abstract public void handleDocumentEvent(DocumentEvent event);

public void changedUpdate(DocumentEvent event) {

handleDocumentEvent(event);

}

public void insertUpdate(DocumentEvent event) {

handleDocumentEvent(event);

}

public void removeUpdate(DocumentEvent event) {

handleDocumentEvent(event);

}

}

Here’s how the class is used to enable the Fahrenheit to Celsius conversion only when there is a number in the Fahrenheit text field:

fahrTextField.getDocument().addDocumentListener(new SimpleDocumentListener() {

public void handleDocumentEvent(DocumentEvent event) {

f2cAction.setEnabled(doubleStringIsValid(fahrTextField.getText()));

}

});

Although the anonymous inner class specification is concise, you are still creating another class. Furthermore, because the behavior must live within a class, it is more difficult to reuse the functionality in multiple places.

In contrast, JRuby supports code blocks and objects such as lambdas that enable specifying the behavior by itself, without requiring the ceremony of creating an entire class to contain it. We exploit this by implementing the JRuby adapter as a class that is instantiated with such a code block or object. Here’s the JRuby implementation of SimpleDocumentListener:

# Simple implementation of javax.swing.event.DocumentListener that

# enables specifying a single code block that will be called

# when any of the three DocumentListener methods are called.

#

# Note that unlike Java, where it is necessary to subclass the abstract

# Java class SimpleDocumentListener, we can merely create an instance of

# the Ruby class SimpleDocumentListener with the code block we want

# executed when a DocumentEvent occurs. This code can be in the form of

# a code block, lambda, or proc.

require 'java'

import javax.swing.event.DocumentListener

class SimpleDocumentListener

# This is how we declare that this class implements the Java

# DocumentListener interface in JRuby:

include DocumentListener

attr_accessor :behavior

def initialize(&behavior)

self.behavior = behavior

end

def changedUpdate(event); behavior.call event; end

def insertUpdate(event); behavior.call event; end

def removeUpdate(event); behavior.call event; end

end

And here’s how it is used:

fahr_text_field.getDocument.addDocumentListener(

SimpleDocumentListener.new do

f2c_action.setEnabled double_string_valid?(fahr_text_field.getText)

end)

Note that unlike Java, where it is necessary to subclass the abstract Java class SimpleDocumentListener, we merely create an instance of the Ruby SimpleDocumentListener with the behavior we want executed when a DocumentEvent occurs. Specifying the code block parameter in the function definition with the ampersand enables passing a code block inline (as above), or passing code in the form of a lambda or proc object as in:

f2c_enabler = lambda do

f2c_action.setEnabled double_string_valid?(fahr_text_field.getText)

end

fahr_text_field.getDocument.addDocumentListener(

SimpleDocumentListener.new(&f2c_enabler))

As with Swing listeners, Swing actions written in Java are implemented as classes, although usually the only thing that differs among them is the behavior specified in the actionPeformed method. (One could argue that a separate class is the appropriate way to express nontrivial processing, but then again if it is nontrivial the bulk of the processing might really belong in a model type class and not the action. This not only makes testing easier, it also makes it much easier to provide an alternate or replacement user or scripting interface; otherwise put, it increases code coherence.) We can therefore employ the same strategy as we did with the document listener. Here is how the exit action is specified in Java:

private class ExitAction extends AbstractAction {

ExitAction() {

super("Exit");

putValue(Action.SHORT_DESCRIPTION, "Exit this program");

putValue(Action.ACCELERATOR_KEY,

KeyStroke.getKeyStroke(KeyEvent.VK_X, Event.CTRL_MASK));

}

public void actionPerformed(ActionEvent event) {

System.exit(0);

}

}

As you see, putValue is used to store key/value pairs in the action. There are multiple options; they are listed in a table at http://java.sun.com/javase/6/docs/api/javax/swing/Action.html.

In Ruby, we create an adapter class that allows specifying the action’s name, options (tooltip text and keyboard accelerator in this case), and behavior:

require 'java'

# When running FrameInRuby, this will generate a warning because

# it is already imported in FrameInRuby. In JRuby, unfortunately,

# imports of Java classes are not confined to the file

# in which they are specified; once you import a class,

# it will be imported for other classes as well.

# This may be fixed in a future version of JRuby.

import javax.swing.AbstractAction

# This class enables the specification of a Swing action

# in a format natural to Ruby.

#

# It takes and stores a code block, lambda, or proc as the

# action's behavior, so there is no need to define a new class

# for each behavior. Also, it allows the optional specification

# of the action's properties via the passing of hash entries,

# which are effectively named parameters.

class SwingAction < AbstractAction

attr_accessor :behavior

# Creates the action object with a behavior, name, and options:

#

# behavior - a behavior can be a code block, lambda,

# or a Proc.

#

# name - this is the name that will be used for the menu option,

# button caption, etc. Note that if an app is internationalized,

# the name will vary by locale, so it is better to identify an action

# by the action instance itself rather than its name.

#

# options - these are hash entries that will be passed to

# AbstractAction.putValue(). Keys should be constants from the

# javax.swing.Action interface, such as Action.SHORT_DESCRIPTION.

# Ruby allows hash entries to passed as the last parameters to a

# function, and they can be accessed inside the method as a single

# hash object.

#

# Example:

#

# self.exit_action = SwingAction.new(

# "Exit",

# Action::SHORT_DESCRIPTION => "Exit this program",

# Action::ACCELERATOR_KEY =>

# KeyStroke.getKeyStroke(KeyEvent::VK_X, Event::CTRL_MASK)) do

# System.exit 0

# end

#

def initialize(name, options=nil, &behavior)

super name

options.each { |key, value| putValue key, value } if options

self.behavior = behavior

end

def actionPerformed(action_event)

behavior.call action_event

end

end

Note the initialize method. The options parameter default to nil, but if any key value pairs are specified, they will be contained in a hash instance named options. The options.each line illustrates a small part of the power of functional programming in Ruby. Iterating over the contents of the hash is clear and concise. For each key value pair, putValue is called with the key and the value, in that order. The whole thing is done only if options is not nil.

Here’s how the exit action is specified in the JRuby program:

self.exit_action = SwingAction.new("Exit",

Action::SHORT_DESCRIPTION => "Exit this program",

Action::ACCELERATOR_KEY =>

KeyStroke.getKeyStroke(KeyEvent::VK_X, Event::CTRL_MASK))

do |event|

java.lang.System::exit 0

end

While this may seem a bit crowded at first glance, notice that you are passing the name, options, and behavior, in that order. In that sense it is a logical and legible call. The => operator aids in visual recognition of the key/value pairs, so it’s easy for the eye to identify the various parts of this call.

You can see that the two hash entries are passed as if they were two separate parameters. However, the function to which they are passed will see them as a single hash instance containing those two key/value pairs. The do/end pair specifies a literal code block which will be seen by the function as the behavior parameter. We could also have passed a variable containing a lambda or a proc.

Although the JRuby features described here require some learning for the Java programmer, that learning is, in my opinion, well worth the cost. The greater conciseness, power, and flexibility of JRuby make writing Swing apps shorter, easier, and of higher quality. And we’ve only scratched the surface of JRuby – there’s much, much more.