Introduction

In this article, we will explore different ways to make HTTP requests in Ruby and compare their performance. We will focus on three approaches: synchronous, threaded, and fiber-based. We will use a simple example of checking the availability of the same URL multiple times. Our tests will measure sending 1 to 256 requests using the different approaches.

Why do I care? I have a Ruby on Rails web site containing many links to YouTube song videos, and they are subject to being pulled by their owner or taken down due to copyright issues. I wanted to automate the checking of these links for availability as a rake task, so that I can run the check with minimal effort from time to time. The links are stored in the project in a YAML file, so it’s easy to read them into memory. However, how would I check them for accessibility?

To simplify the examples below, instead of fetching the real URL’s, I will fetch the same URL multiple times. I’ll use a URL built with "https://httpbin.org/delay/#{sleep_seconds}" to access the Internet and simulate the response delay with a sleep on the server. The examples will return an array containing the responses.

The Synchronous Approach

I started out the simple and conventional way, using Net::HTTP:

def get_responses_synchrously(count)

logger.debug("Getting #{count} responses synchronously")

count.times.with_object([]) do |_n, responses|

responses << Net::HTTP.get(URI(url))

end

end

However, the time it took was frustratingly long. How could I make this faster?

The Thread Approach

Having been a fan of threads for a long time, this was the next thing I tried. Since the number of links was just a few dozen, this number was low enough that creating a thread for each link was feasible. Note that we still use Net::HTTP.get, but each call runs in its own thread. Fortunately, Net::HTTP.get supports threaded use by yielding its thread’s control after sending the request, thereby avoiding CPU time waste while waiting for the response:

def get_responses_using_threads(count)

logger.debug("Getting #{count} responses using threads")

threads = Array.new(count) do

Thread.new { Net::HTTP.get(URI(url)) }

end

threads.map(&:value)

end

As you can guess, this was way faster.

The Fiber Approach

I wasn’t done though – recently I finally got around to learning about Ruby fibers, and wanted to try them here. Rather than write the low level Fiber code myself, it was simpler to use @ioquatix’s (Samuel Williams’) excellent async Ruby gems (I needed async and async-http) to handle the low level plumbing. The resulting code was more complex than the previous two approaches, but not too bad (run gem install async-http if necessary):

def get_responses_using_fibers(count)

logger.debug("Getting #{count} responses using fibers")

responses = []

Async do

begin

internet = Async::https::Internet.new(connection_limit: count)

count.times do

Async do

begin

response = internet.get(url)

responses << response

ensure

response&.finish

end

end

end

ensure

internet&.close

end

end.wait

responses

end

The magic is in the Async framework and Async::https::Internet’s get method, which is fiber-aware and yields control of the CPU while waiting for a response.

Comparing the Performance Results

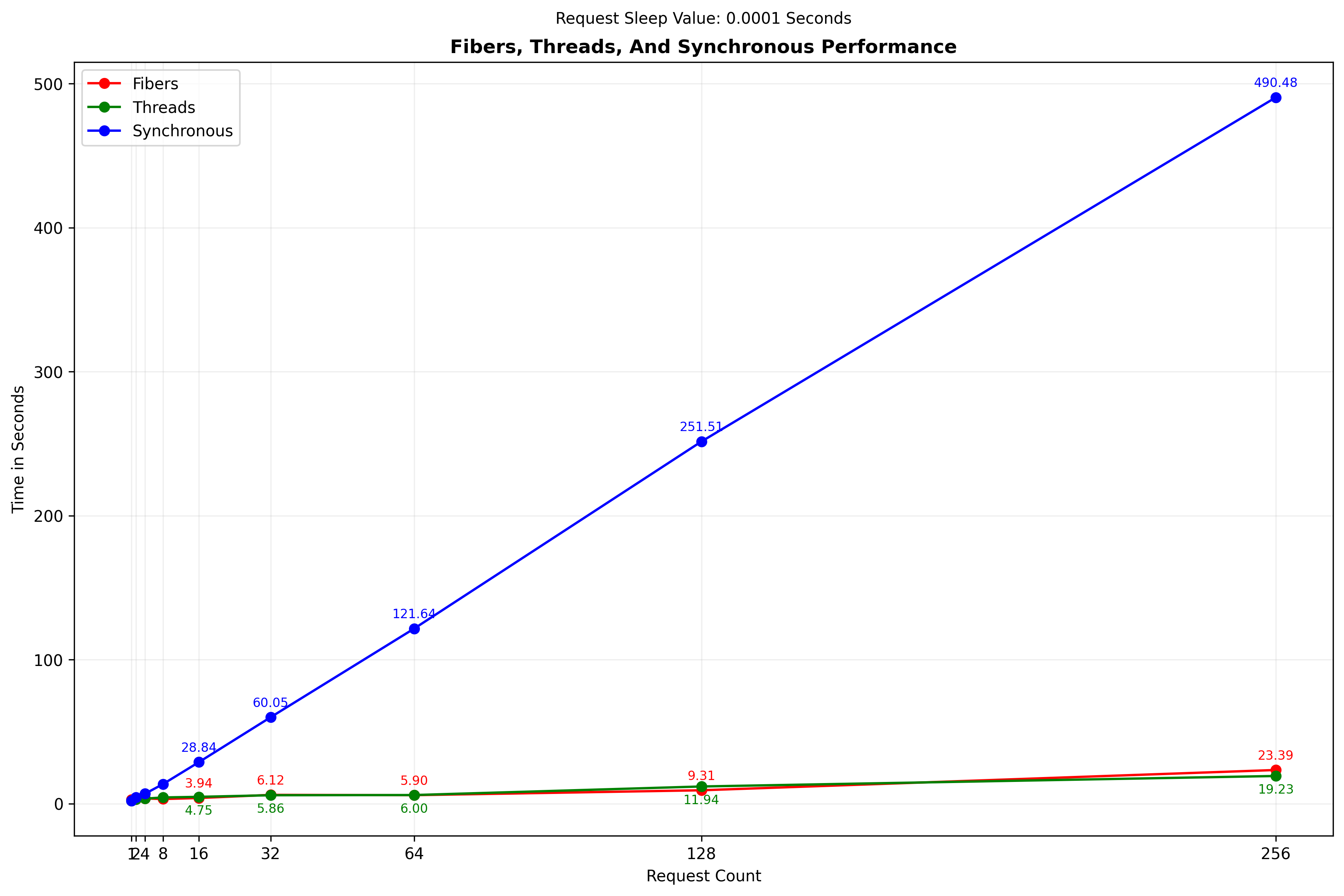

I did a benchmark comparing the results of fetching request counts for powers of 2 ranging from 1 to 256 (1, 2, 4, 8, 16, 32, 64, 128, and 256).

Here are the results comparing all three approaches, using the averages of several test runs:

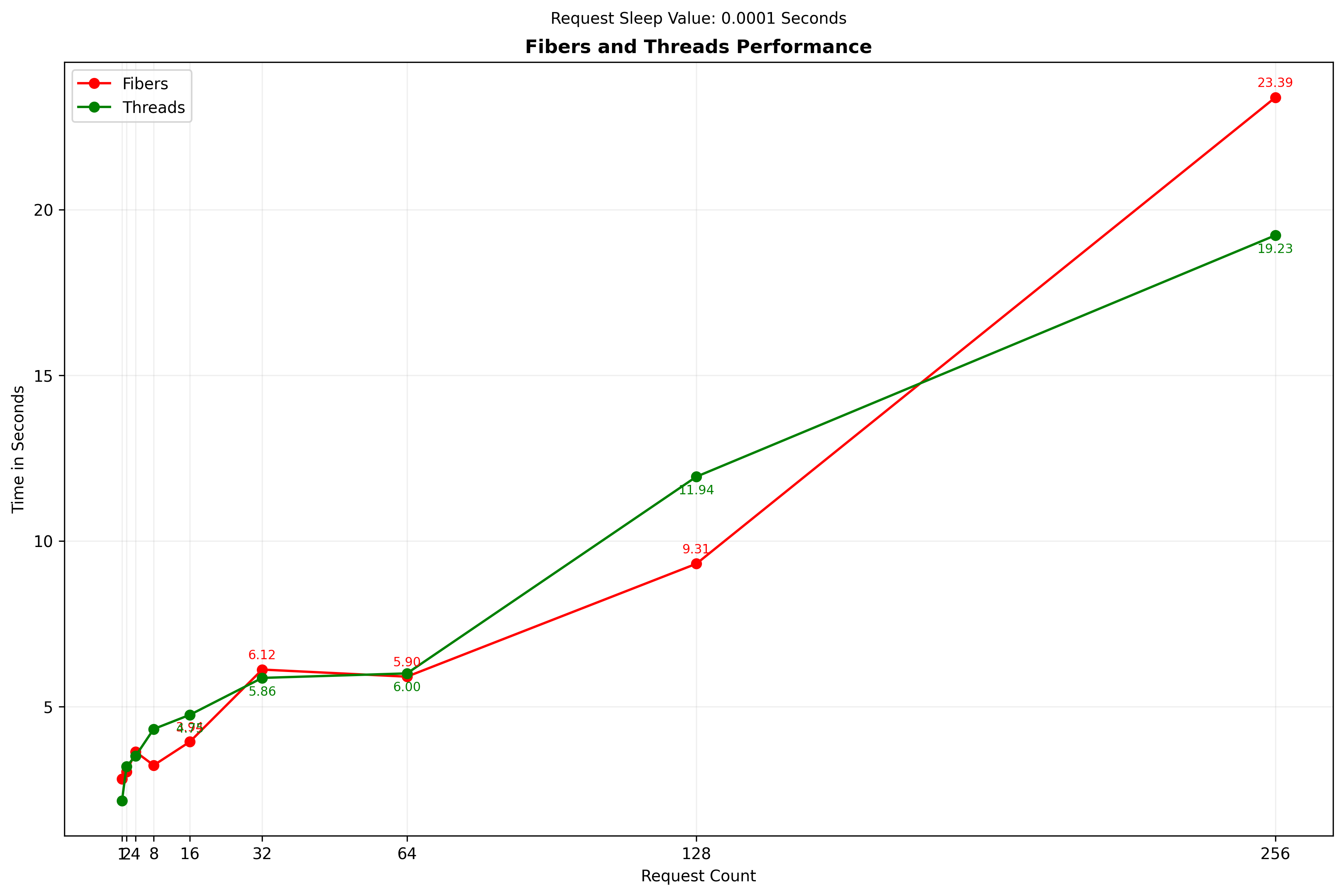

As expected, the synchronous approach was by far the slowest, since only one request could be active at any given time. Both the thread and fiber approach were dramatically faster, and not that different from each other. To zoom in on the difference between the thread and fiber approach, this graph omits the synchronous approach:

What do we make of this though? Which should we choose to use?

Fibers vs. Threads

If one knows that the numbers will always fall within the bounds of 1 to 256, then it probably doesn’t much matter which to use. However, if there is a possibility of higher request counts, then fibers make more sense. Here are some ways in which threads and fibers differ:

Threads:

- OS-Mapped: In Ruby versions 1.9 and later, Ruby threads are mapped to operating system threads. Each thread has its own dedicated stack and other resources allocated by the OS.

- Context Switching Overhead: Switching between threads involves saving and restoring the entire execution context (registers, stack pointers, etc.), which is a relatively expensive operation.

- System Limits: The operating system typically imposes limits on the number of threads a process can create due to resource constraints.

Fibers:

- User-Level: Fibers are a user-level construct managed entirely within the Ruby interpreter. They share the same stack and other resources with the thread they’re running in.

- Cooperative Scheduling: Fibers explicitly yield control to each other, making context switching much faster and less resource-intensive.

- Lightweight: Due to their cooperative nature and shared resources, fibers have a much smaller memory footprint than threads.

Operating System Open File Handle Limits

A file handle (aka “file descriptor”) is an object (typically a small non-negative integer) stored in a variable on the OS level used to refer to a resource, which can be a file, pipe, socket, or terminal. The OS restricts the number of file handles that can be used by a given process. In our testing, we need to stay within or increase that limit.

In general, the synchronous approach results in only one file handle being used at a time for all the requests. In contrast, the thread and fiber approaches may theoretically use file handles for all the requests at the same time, since they do not wait for one to finish to start another.

Even with as few as 256 simultaneous requests, the operating system session’s file handle limit may be exceeded. If you get an error saying that all the process’ file handles have been used, in Linux and Mac OS you can use ulimit to increase the maximum file handle count (used for both files and network sockets) for the terminal session, and then rerun the program. For example: ulimit -n 2048 && my-program. However, ulimit will only do this successfully if the systemwide maximum file count is large enough to accommodate it.

Threads are far more heavyweight than fibers, so for large request counts, one would need to implement some kind of thread pooling, and this would probably result in far fewer requests per second than fibers. Sam Williams posted a YouTube video (RubyConf Taiwan 2019 - The Journey to One Million by Samuel Williams - YouTube) in which he showed one million fibers running network requests!

JRuby

No discussion of Ruby concurrency is complete without a reminder that even with multiple threads, C Ruby’s Global Interpreter Lock (aka “the GIL”) guarantees that only one CPU can be used at a time. In contrast, JRuby (Ruby running on the Java Virtual Machine), threads do run truly concurrently, on multiple CPU’s. This can make threading in JRuby much more performant.

That said, these requests are not making heavy use of the CPU, and JRuby threads (really, Java threads) are still far more heavyweight than fibers, so even with JRuby fibers may be the better choice.

Large Request Counts

This article covered small numbers of requests, but what if you need to make thousands or millions of requests? In that case,

-

Thread Pooling: If you are using threads, you may need to implement a thread pool to limit the number of threads created and manage the requests.

-

Fiber Pooling: If you are using fibers, you may need to implement a fiber pool to limit the number of fibers created and manage the requests.

-

Async Gems: If you are using fibers, you may want to consider using the

asyncgems to handle the low-level plumbing for you. This will make your code simpler and more maintainable, but will add a dependency to your project. -

Operating System Limits: Be aware of the operating system’s file handle limits and ensure that you stay within them.

-

JRuby: If you are using JRuby, you may be able to take advantage of true concurrency with threads.

-

Performance Testing: Thoroughly test your code with the expected number of requests to ensure that it performs as expected.

-

Error Handling: Ensure that your code handles errors gracefully and does not crash when an error occurs.

-

Logging: Add logging to your code to help you diagnose issues and monitor performance.

-

Code Complexity: Consider the complexity of your code and choose the approach that is simplest and easiest to maintain.

-

Code Review: Have your code reviewed by a colleague to ensure that it is correct and follows best practices.

-

Documentation: Document your code to make it easier for others to understand and maintain.

-

Testing: Write tests for your code to ensure that it works as expected and to catch any regressions.

-

Performance Monitoring: Monitor the performance of your code in production to identify any bottlenecks and optimize as needed.

Conclusion

Which approach to use depends on a number of factors:

- What will be the average request count?

- What will be the maximum request count?

- How often will this be used?

- How important is faster completion?

- Do I want or need to avoid the additional dependency of the async gems?

- How important is code simplicity?

Thorough research may be necessary to determine the very best approach for any given situation, but here is one policy that balances performance and simplicity:

| Request Count | Approach |

|---|---|

| n <= 3 | Synchronous |

| 4 <= n <= 16 | Threaded |

| n > 16 | Fiber |

Addendum

The complete Ruby program used to measure request performance can be found at https://gist.github.com/keithrbennett/719af73894458a4378aa3e3a5cc9b70a and is also pasted here:

#!/usr/bin/env ruby

# frozen_string_literal: true

# IMPORTANT: You may need to increase the number of available file handles available to this process.

# The number should be greater than the maximum number of requests you want to make, because each process

# opens at least 3 file handles (stdin, stdout, stderr), and other files may be opened during the program's

# run (e.g. for the logger).

# ulimit -n 300 && scripts/compare_request_methods.rb

require 'async/http/internet' # gem install async-http if necessary

require 'awesome_print'

require 'benchmark'

require 'json'

require 'logger'

require 'net/http'

require 'pry'

require 'yaml'

# These are the external gems that must be installed for the program to run.

REQUIRED_EXTERNAL_GEMS = %w[async-http awesome_print pry].freeze

Thread.abort_on_exception = true

Thread.report_on_exception = true

class Benchmarker

attr_reader :logger, :request_count_per_run, :sleep_seconds, :url

def initialize(request_count_per_run, sleep_seconds, logger)

@request_count_per_run = request_count_per_run

@sleep_seconds = sleep_seconds

@logger = logger

@url = "https://httpbin.org/delay/#{sleep_seconds}"

end

def get_responses_synchrously(count)

logger.debug("Getting #{count} responses synchronously")

count.times.with_object([]) do |_n, responses|

responses << Net::HTTP.get(URI(url))

end

end

def get_responses_using_threads(count)

logger.debug("Getting #{count} responses using threads")

threads = Array.new(count) do

Thread.new { Net::HTTP.get(URI(url)) }

end

threads.map(&:value)

end

def get_responses_using_fibers(count)

logger.debug("Getting #{count} responses using fibers")

responses = []

Async do

begin

internet = Async::https::Internet.new(connection_limit: count)

count.times do

Async do

begin

response = internet.get(url)

responses << response

ensure

response&.finish

end

end

end

ensure

internet&.close

end

end.wait

responses

end

def self.call(request_count_per_run, sleep_seconds, logger)

self.new(request_count_per_run, sleep_seconds, logger).call

end

def output_results(results)

logger.info('-' * 60)

logger.info(results.to_json)

ap(results)

end

def call

logger.info("Starting run with #{request_count_per_run} requests each sleeping #{sleep_seconds} seconds")

results = {

time: Time.new.utc,

sleep: sleep_seconds,

count: request_count_per_run,

fibers: Benchmark.measure { get_responses_using_fibers(request_count_per_run) }.real,

threads: Benchmark.measure { get_responses_using_threads(request_count_per_run) }.real,

synchronous: Benchmark.measure { get_responses_synchrously(request_count_per_run) }.real,

}

output_results(results)

results

end

end

class Runner

def self.call() = new.call

def setup_logger

logger = Logger.new('compare_request_methods.log')

logger.level = Logger::INFO

logger.info('=' * 60)

logger

end

# Measure the time it takes to run a block of code

# @return [Array] The return value of the block and the duration in seconds

def time_it

start_time = Process.clock_gettime(Process::CLOCK_MONOTONIC)

return_value = yield

end_time = Process.clock_gettime(Process::CLOCK_MONOTONIC)

duration_in_seconds = end_time - start_time

[return_value, duration_in_seconds]

end

def write_results(logger, results, duration_secs)

timestamp = Time.now.utc.strftime('%Y-%m-%d-%H-%M-%S')

File.write("#{timestamp}-results.yaml", results.to_yaml)

logger.info(results.to_json)

puts("Done. Entire suite took #{duration_secs.round(2)} seconds.")

end

def call

counts = [1, 2, 4, 8, 16, 32, 64, 128, 256]

logger = setup_logger

puts "Starting run with counts: #{counts.join(', ')}"

results, duration_secs = time_it do

counts.map { |count| Benchmarker.call(count, 0.0001, logger) }

end

write_results(logger, results, duration_secs)

end

end

class GemChecker

def self.call(required_external_gems) = new.ensure_gems_available(required_external_gems)

def gem_exists?(gem_name)

begin

gem(gem_name)

true

rescue Gem::MissingSpecError

false

end

end

def find_missing_gems(required_gems)

required_gems.reject { |name| gem_exists?(name) }

end

def ensure_gems_available(required_external_gems)

missing_gems = find_missing_gems(required_external_gems)

if missing_gems.any?

puts "Need to install missing gems: #{missing_gems.join(', ')}"

exit(-1)

end

end

end

GemChecker.call(REQUIRED_EXTERNAL_GEMS)

Runner.call